How Are the CEOs of Health Nonprofits Among the Richest People in the U.S.? Two Words: Phantom Stock.

A fascinating and disturbing story about how some healthcare nonprofits exploit tax loopholes and fabricate imaginary stock prices to ensure their CEOs can afford those lavish yachts and private jets.

A fascinating and extremely disturbing story about how some U.S. healthcare nonprofits exploit tax loopholes and fabricate imaginary stock prices to ensure their CEOs can afford those lavish yachts and private jets. 🚤✈️

Everyone knows that to become Jeff Bezos-rich or Elon Musk-rich, cash pay is not enough. You need equity. You need stock. You need stock-based compensation, such as stock options. Then there are a lot of forces working in your advantage: stock’s magic of compounding, options’ non-linear (think exponential) payoff and so many different ways to minimize or avoid taxes, such as trusts and deferred compensation - things you can’t get with just cash. It’s a beautiful thing.

For instance, according to a recent in-depth investigation by Stat News, 79% of total CEO compensation of the largest 7 healthcare insurance companies is stock and stock-based financial instruments. For example, Cigna’s CEO became a billionaire purely from Cigna’s compensation.

But what if you’re a CEO of a nonprofit and really want to have the same private jet that Taylor Swift is flying on or the same yacht that Larry Ellison is riding on, but those pesky IRS rules don’t allow you to get rich because, well, it’s a nonprofit.

Say no more. We at Wall Street Bros created a clever “get rich quick” trick for CEOs just like you. 💰💰💰

How do CEOs get rich? Well, through stock and stock options, of course.

But wait, nonprofits aren’t supposed to issue stock because they are not profit-maximizing entities, by definition, right?

Well, there is a clever financial trick to solve that problem and to exploit the IRS loophole.

Introducing: phantom stock.

Phantom stock is not real stock. It’s fake stock, where you set your own stock price and issue as many shares as you want. There are no shareholders to complain about stock “dilution” and other ethical issues because, well, the stock is a product of your imagination.

While the stock is fake, the money is real.

And just so everyone thinks this is legit, we're going to come up with a different name that sounds legal-ish. How about “non-qualified deferred compensation”? It has the word “compensation” in it and it doesn’t have the word “stock”. That’s how you trick the regulators. Clever, huh?

Is phantom stock legal? Enough with the questions. Do you want the private jet or not?

1. What Exactly is Phantom Stock? And Why is it Such a Sweet, Yet Semi-Legal, Form of Executive Compensation for Healthcare Nonprofits?

Why is executive compensation at some nonprofit organizations among the highest in the country? Two words: phantom stock. It’s a semi-legal way to pay executives, fraught with conflicts of interest, being utilized, for instance, by Mayo Clinic, Fidelity Charitable, and many other nonprofit organizations.

The largest part of the executive compensation in these organizations is not cash. It’s incentive-based compensation, such as “phantom stock,” the price of which is decided by - drum roll - the executives themselves!

So what is phantom stock? And why is it so attractive to executives, but not so much for anyone else at the nonprofit organization? (Sources: RSM, Investopedia.)

1️⃣ Phantom stock, commonly known as “non-qualified deferred compensation” (NQDC), is a fake stock price constructed by the organization’s management based on arbitrary metrics. There is no real stock price. While for public companies, the stock price is “voted on” by millions of investors every nanosecond and can potentially dramatically go up or down, the stock price at nonprofit organizations is based on some theoretical “incentive” formula and is typically very predictably gradually going up. This formula is usually selected to be non-volatile on purpose. The executives argue, often hypocritically, that earnings are not a goal for a nonprofit, so the formula should be based on things like the number of patients, the amount of charitable donations, or the asset base. The “stock price” is usually set quarterly, or whatever the reporting period is. Just like with public companies, this fake phantom stock could also have so-called “stock options” which are an even faster way for the executives to get richer.

2️⃣ Phantom stock and stock options have a vesting period, typically one to three years. Then they have a pretty long exercise period, typically up to 10 years, when the CEO and other executives can sell their phantom stock and exercise their options whenever they please.

3️⃣ It’s important to note that while the phantom stock exercise flexibility makes this optionality very valuable to executives, inversely, it could be quite a burden for the whole organization and its members (such as patients and physicians) because the desire of a CEO to cash out in order to buy a new yacht may not necessarily be the best time for the organization to incur such expense. In this regard, the term “non-qualified” means that, unlike traditional deferred compensation, phantom stock cannot be expensed at the time it is granted (i.e., typically at its lowest value), but rather, at the time when the CEO decides to cash out, putting a financial burden on the organization. It’s a zero-sum game: if the CEO cashes out big, the organization has to pay.

4️⃣ Phantom stock compensation is a great tax deferral mechanism for executives. As you know, executives use all sorts of tax loopholes to avoid paying taxes, such as the Grantor Retained Annuity Trust (GRAT) and other accounting schemes. But here, you can defer your taxes into the future because the made-up “stock price” is almost guaranteed to be going up.

5️⃣ Unlike public companies, which may face outrage from their shareholders for “share dilution,” nonprofits, since there is no real stock, can issue as many shares to their executives as they want (and they want a lot!). No one would ever complain because the shares are artificial (but the money is real!).

6️⃣ Phantom stock is a great tool for executives to keep regulators off their back. If you pay a CEO $50 million in cash, you may face serious questions from the IRS or the SEC. But if you pay a CEO $50 million in “incentive compensation” (or some other bullshit term these organizations may use), you are safe because the compensation is based on a “preset formula”. (Of course, never mind that the executives themselves “preset” the formula.)

7️⃣ NQDC was originally put forward by the IRS (code section 457) as a type of retirement plan that would provide supplemental retirement benefits to an executive. However, as the “retirement” part was only a recommendation, some nonprofits have been abusing this program offering their executives the flexibility of cashing out before retirement, and in fact, at any time the executive finds convenient.

While phantom stock has made executives of nonprofit healthcare organizations some of the richest people in the country, nothing still beats the Cigna CEO’s $1 billion (!) payday.

2. Free Advice to the SEC: Examine the Volatility of Comp Numbers

As you may be aware, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) not only overlooked Madoff’s crimes due to its incompetence, but it also consistently dismissed whistleblower Harry Markopolos’ detailed account of Madoff’s crimes since 1999. As argued by Markopolos and his colleague Dan diBartolomeo, to identify potential criminal activity, there was no need for an in-depth analysis of Madoff’s “accounting”. A simple review of his returns would have sufficed: there was no volatility! Every reporting period, returns were “smooth” and positive, an outcome that would have been impossible with the actual portfolio.

In the context of executive compensation for nonprofits, detecting the existence of phantom stock is straightforward, as I elaborate below. One simply needs to observe the volatility (i.e., spikes) in the compensation reported on the executive’s W-2 forms. Executives, driven by greed, would eventually want to liquidate their fictitious phantom stock - perhaps to fund an impulsive purchase of their tenth house or third yacht. This is when a spike in reported compensation becomes evident.

In other instances, CEOs adopt a more clever approach. They attempt to sell their phantom stock in a more “smooth” manner. In such cases, the SEC (and the IRS) might want to examine the dollar magnitude of the figures.

It’s not that complicated.

3. Case Studies

Let’s examine six instances involving healthcare organizations where the executives may have lost sight of their nonprofit organizations’ mission. All the data is publicly available, sourced from the Form 990 that every U.S. 501©(3) tax-exempt organization must file annually.

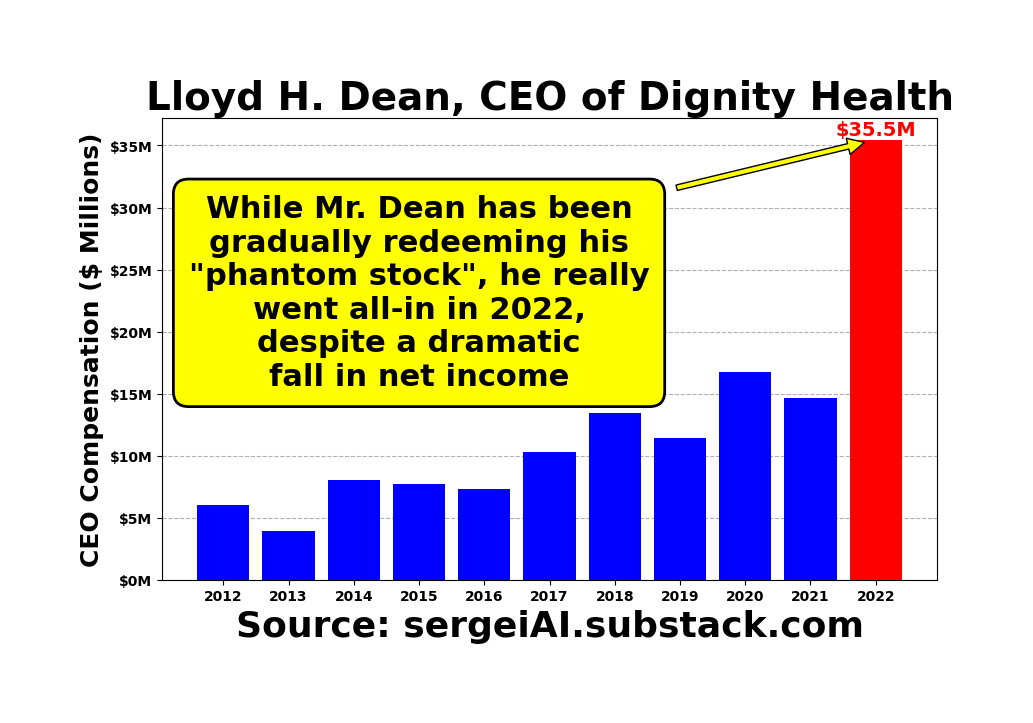

3.1. Lloyd H. Dean, CEO of Dignity Health: $35.5 Million

According to its most recent tax filing, “Dignity Health is committed to making the healing presence of God known in our work by improving the health of the people we serve, especially those who are vulnerable, while we advance social justice for all.” (Sources: ProPublica, MSN.) Certainly, Dignity Health’s CEO, Lloyd H. Dean, and other executives feel the material presence of all that cash. In fact, as of its most recent 2022 tax filing, the executive compensation represents a mind-boggling 74% of its net earnings.

3.2. Howard P. Kern, CEO of Sentara Health: $33.2 Million

According to its website, “Sentara Health is committed to always keeping patients safe, treating them with dignity, respect, and compassion, listening and responding to them, keeping them informed and involved, and working together as a team to provide quality healthcare.” Apparently, this doesn’t prevent its CEO, Howard P. Kern, from becoming one of the richest people in the industry.

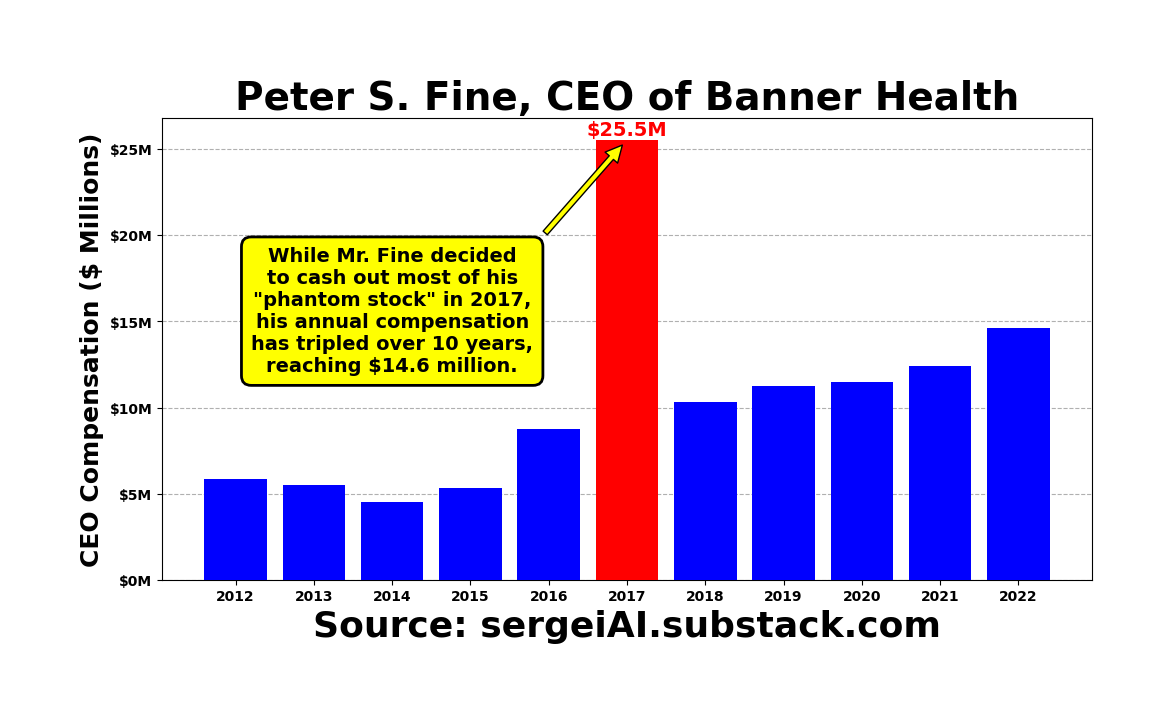

3.3. Peter S. Fine, CEO of Banner Health: $25.5 Million

According to its website, “as a nonprofit, Banner Health exists to provide health care services to the communities it serves, rather than generate profits.” They seriously could’ve tricked me with this statement. They’ve actually been running like a for-profit organization, and Mr. Peter S. Fine is doing just fine because of that, thank you very much.

3.4. Ernie W. Sadau, CEO of Christus Health: $17.9 Million

According to its most recent tax filing, Christus Health’s mission is “supporting the health care ministries of the sponsoring congregations in extending the healing ministry of Jesus Christ in conformity with the Roman Catholic Church.” That has not prevented its CEO and other executives from being paid handsomely, even when the organization was losing money. In fact, as of its most recent 2022 tax filing, the executive compensation represents a whopping 54% of its net earnings.

3.5. Craig B. Thompson, CEO of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center: $8.1 Million

According to its website, “We [at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center] inspire trust by having the courage to say what we mean, matching our behaviors to our words, and taking responsibility for our actions. We value and support transparency, knowing that open, honest communication is critical to our success.” If they are so transparent, perhaps they could explain why there was an almost 3-fold jump in their CEO’s most recent compensation number, despite the 50% drop in net earnings. I’m being facetious - of course, we know why: The CEO cashes out his stock whenever he is pleased.

3.6. James D. Dahling, CEO of Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters: $8.9 Million

According to its most recent tax filing, Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters is “dedicated to the mission of providing the best possible care and services for all children who come to us because of sickness and injury.” That’s an honorable mission. However, I question, what exactly did Mr. James D. Dahling sell in 2020 to generate such a spike in his already pretty hefty compensation.

It’s worth noting that James D. Dahling retired at the end of 2022.

4. But Wait… What Is the Mission of Healthcare Nonprofits Anyway?

The mission of healthcare nonprofits is multifaceted, reflecting the diverse needs and challenges within the healthcare sector. These so-called IRS Section 501©(3) tax-exempt organizations are supposed to play a critical role in addressing gaps in healthcare delivery, research, and education, often focusing on areas that are underfunded or neglected by the private and public sectors.

Nonprofit organizations, including healthcare nonprofits, can indeed make a profit. However, the key difference between nonprofits and for-profit organizations is that a nonprofit organization cannot distribute its profits to any private individual. Instead, according to the National Council of Nonprofits, the profits are typically used in the following four ways:

1️⃣ Reinvested in the Organization: The profits can be reinvested back into the nonprofit to further its mission. This could include expanding existing programs, starting new initiatives, or enhancing the organization’s infrastructure.

2️⃣ Building a Reserve Fund: Nonprofits should try to have some level of positive revenue to build a reserve fund to ensure sustainability.

3️⃣ Paying Reasonable Compensation: Nonprofits may pay reasonable compensation to those providing services. This includes salaries for staff members, fees for contractors, and other operational expenses. (Note that executive compensation is not mentioned at all.)

4️⃣ Donated to Other Nonprofits or Beneficiaries: In some cases, the profits might be donated to other nonprofit organizations or directly to the beneficiaries that the nonprofit serves.

Remember, the idea behind these rules is to require charitable organizations to dedicate as much income as possible to the charitable purpose they purport to serve. This is because tax-exempt charitable nonprofits are formed to benefit the public, not private interests. (Sources: National Council of Nonprofits, Forbes, Legal Zoom.)

Many academics argue that healthcare nonprofits have their role in a society beyond the provision of “free care”. They argue that focusing only on the free care they provide and ignoring nonprofit hospitals’ contribution to the public good would exacerbate harm and inequality in the current system. For instance, a brand new JAMA paper discusses the critical issue of nonprofit hospital tax exemptions, arguing against proposals that condition these exemptions on the provision of free care. It highlights the complexities and unintended consequences of such measures, emphasizing that nonprofit hospitals play a vital role beyond just providing free care, including promoting public health and offering various community benefits. The piece advocates for improving nonprofit hospital accountability through better governance and fiduciary responsibilities, rather than imposing restrictive free-care requirements that could lead to financial distress for hospitals and reduced services for underserved populations.

5. Are All Healthcare Nonprofit CEOs Crazily Rich?

While there are clear outliers, it’s not accurate to say all healthcare nonprofit CEOs are exorbitantly rich. In fact, most nonprofit executives appear to take their job very seriously and maintain reasonable compensation. Being reasonable means:

🔹Adhering to the mission of the nonprofit organization as mentioned above.

🔹Having a “reasonable compensation” as defined by the IRS. This typically involves comparison with peer organizations, excluding the outliers such are the ones mentioned earlier. Most nonprofit healthcare organizations compensate their executives in cash. If deferred compensation is offered, it follows the traditional model - expensed at the grant date (i.e., at its lowest value). This compensation could accrue interest or be indexed for inflation, but does not include anything akin to “phantom stock.”

6. My Take

What’s happening in the boardrooms of some of the largest nonprofit healthcare organizations in the world is terrifying. Since these entities are not publicly traded, executives create their own “sandbox” stock market. In this market, prices almost always go up, and the number of shares issued to executives seems almost infinite. This occurs because there are no real shareholders to complain about stock dilution and implement other ethical checks and balances. This semi-legal practice, crafted by Wall Street bros, is known as phantom stock. Often, it forms the largest portion of executive compensation. It begs the question: Where are the SEC and the IRS looking? These nonprofit organizations are granted tax-exempt status for a reason. Yet, they appear to be engaged in dubious practices, developing creative financial compensation schemes for their executives and competing over whose nonprofit CEO is wealthier. I’m truly disgusted.

In their pursuit of dollars, some healthcare nonprofits have neglected their mission. By legal statute, they are NON-profit and are supposed to serve patients, physicians, and the community, not enrich the executives.

I hope my analysis, the first of its kind, will bring to light the severe situation present in this country within some nonprofits.

👉👉👉👉👉 Hi! My name is Sergei Polevikov. In my newsletter ‘AI Health Uncut’, I combine my knowledge of AI models with my unique skills in analyzing the financial health of digital health companies. Why “Uncut”? Because I never sugarcoat or filter the hard truth. Thank you for your support of my work. You’re part of a vibrant community of healthcare AI enthusiasts! Your engagement matters. 🙏🙏🙏🙏🙏

Why are boards of directors of healthcare nonprofits approving these lavish compensations for their CEOs?

Two main reasons:

1. Boards are in bed with CEOs, merely implementing a "tit for tat" arrangement. To understand this, it's crucial to trace back to how board members were selected in the first place. Typically, this is done by a nominating committee, where the CEO either has a direct vote or direct input. Remember, being a board member of a large healthcare nonprofit is a well-paid position. Thus, the board (specifically, the compensation committee of the board) is merely returning the favor to the CEO by granting this lucrative compensation. This represents a major conflict of interest, and it's perplexing why both the SEC and the IRS remain silent.

2. As I mentioned in the article, the initial compensation award is often a fraction (often 3, 5, or 10 times smaller) of what's reported in Form 990. This discrepancy arises because a significant portion of the executive compensation is deferred compensation. Specifically, phantom stock, which is fake stock whose price almost always increases, is classified as "non-qualified deferred compensation" (NQDC). It's reported on the executives' W-2 report and on Form 990 when they decide to sell the phantom stock to purchase that 11th house or private jet. They can sell whenever they wish, and the nonprofit must immediately come up with the cash, potentially straining the organization. Therefore, what's reported to the IRS as executive compensation is the price (the amount) at which they SELL their stock, not the price at which they RECEIVE the stock, which could be two very different numbers.

Related articles:

1. There are 57 people working at nonprofit organizations in Cleveland who make more than $1 million a year. 56 of them work in healthcare: https://www.cleveland.com/news/2024/01/nonprofit-millionaires-top-57-paid-greater-cleveland-nonprofit-employees-predominately-in-healthcare.html.

2. $1 Million-a-Year charitable hospital executives in Connecticut who may not need holiday gifts: https://healingandstealing.substack.com/p/connecticuts-fortunate-forty.

3. The CEO of Ascension moved over to a hedge fund and is paying himself $12 million a year to manage the investment: https://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2024/02/05/the-moneys-in-the-wrong-place-how-to-fund-primary-care/.